Blog home »

The Job Market (Parts I, II, III, & IV)

Note: I'm happy to edit and polish this over time, so feel free to send me questions or comments. Also, this post contains sprinklings of snark, as is necessary post-job-market-experience. Please approach with a sense of humor.

I was on the faculty job market this past year, 2021, during the COVID-19 pandemic and while everything was on zoom, and am writing this about my experience in response to many questions that I've gotten, not because I think I am any kind of expert.

Index

- My Timeline

- Multiple Markets

- Where to Apply and Getting Organized

- Recommendation Letters

- Application Materials

- Screening Calls

- Scheduling Interviews

- Zoom Interview Tips

- The Job Talk

- One-on-One Interviews

- After You Get Offers: Declining, Withdrawing, Extending

- Second-visits

- Negotiating

- Decisions

- Part IV: Perspective from Current Faculty

Blog home »

Part I

September 28, 2021

I was hoping to write an all-encompassing post, but time keeps passing, so I'll start with the parts that are relevant now and update with more later so as not to miss out on this year's cycle.

My first suggestion, which isn't much use to just say, is that being on the job market is a year of constant decision-making and being placed in stressful positions. People tend to start from a place of anxiety and consulting their friends and mentors about every little thing, and eventually wind up in a semi-numb/zen place where they toss off emails, take meetings, and give talks like it's no big deal. The sooner you can get to that independent and zen place, the better, because the year is really just a perpetual state of people throwing insane-situation darts at you, so it's time to become impervious to it and learn to just enjoy the chaos. It sort of reminds me of electrical stimulation during physical therapy—when you have a really painful injury, they electrically stimulate your nerves. At first it's uncomfortable and even slightly painful as they increase the frequency to stimulate the nerves of your injury which are overworked, but eventually, they're so stimulated that they finally go numb and rest and you get some relief, and it's kind of the best thing ever. That's where we need to get to—past that initial anxiety stimulation and to the rest and relief.

One of the first things you learn as new faculty is that no one really knows what they're doing. Think about it: if you're on the job market, you're going to be faculty in a few short months. People start teaching immediately, advising, and get asked to be on admissions and hiring committees. There's no separate training for that. That's you in a few month's time. That could be you right now if you'd gone on the market last year. So who's on the other side of your process? You, effectively. Pretty much the best thing you can do whenever you start stressing and asking yourself questions about every small thing is imagine you're on the other side. What would you care about if you were hiring? Would you decide whether to hire someone because they wore a blue vs. pink shirt, or skipped a glass of wine at dinner? No, I don't think so, so you don't need to stress about that. What would you look for in a colleague? Giving yourself this mental check has given me a new level of zen whenever I interact with anyone, apply for anything, etc.

My Timeline:

Part of this will be non-standard due to COVID, and also, I didn't necessarily do a good job (which I'll try to point out), but might be a helpful reference.- April-August: Was anxious about the job market and asked questions about how to prepare to my mentors and they kept telling me it was too early, to just do research and relax. This was good advice.

- Aug 1: I started making sure my website really comprehensive.

- Aug 11: My advisor suggested that I give a few research area seminars in the fall.

- Aug 24: I started really considering my service load for the year and making sure not to take on too much.

- Aug 27: My advisor and I settled on some seminars and reached out to organizers.

- Sept 4: I first discussed letter writers with my advisor.

- Sep 13-23: First attempts at research and teaching statements (mostly because of applications to "Rising Stars").

- Sept 21: Gave first seminar talk, included full day of one-on-ones (with people in my research area), which was great practice for an interview.

- Sept 23: SigECOM job market profiles were due, which is an aggregation of people on the job market in my research area. Make sure you get on these if they exist in your area!

- Oct 23-27: Decided on and asked letter writers (advised by PhD advisor and postdoc host). This was late. Ask for letters and work on statements closer to Sept 15.

- Oct 26-Nov 4: Major work on statements. Also started canceling research meetings to focus on job market things.

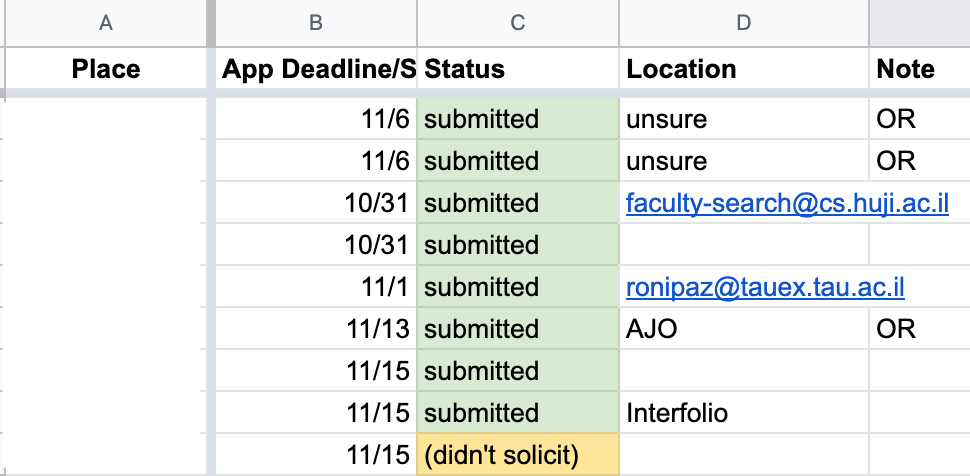

- Nov 5-6: Submitted my first applications. Note that adjusting cover letters and uploading documents still takes a surprising amount of time, so even though I started on the 5th, it took two days to finish my first batch. This was late, both for Israel and the OR market. They really should have been in by October 15.

- Nov 8-11: Informs—must attend if on the OR market, and should have OR applications in beforehand.

- Nov 9-10: Rising Stars in EECS, a fantastic workshop for women in EECS. Many attend before the year that they're on the market. I highly recommend waiting until you're on the market, because they actually give feedback on statements and talk intros and give advice for intros which will not be useful if you're not actually on the job market.

- Nov 25: First OR screening call (until Dec 14).

- Dec 18: First US CS Screening call (until Jan 19).

- Dec 31: First Israel Interview (until Feb 2). These were a bit later than typical because of my late applications.

- Jan 15: First OR interview. I delayed this about a week due to existing Israel interviews.

- Jan 19: First rejection email.

- Jan 21: First US CS interview (until March 11). I scheduled these as early as possible to try to align with the Israel and OR markets, so they were a bit earlier than usual.

- Feb 1: First Israel offer (until Feb 17), made formal Feb 18, one month deadline.

- Feb 1: First OR offer, made formal Feb 14, 3 week deadline.

- Feb 9: First US CS offer (until March 27). The first formal CS offer letter I received was on March 25, though. The shortest deadline I had was two weeks, which eventually got extended to three. These were for three different schools.

- March 15: First second visit (until April 7).

- April 9: Date of my decision.

Multiple Markets

I applied to three different markets: the North American Computer Science market (which I'll just refer to as the US CS market, or just CS, since I only actually applied to one school in Canada), the Operations Research (OR) market, and the Israel (Computer Science) market. Each market has slightly different timing and traditions, so I sought advice from people within each market. It's important to do this earlier on so that so that it's clear that you respect the market and really want to be a part of it.For example, if you are going on the OR market, you need to attend Informs, the big annual OR conference. The year of the job market, you give a talk and everyone interested in hiring you should come see it. You also have interviews at Informs. In order to prepare for this process, it's best if you attend Informs a previous year to understand what this event looks like, because it's definitely not your typical CS conference. Also, it's a journal field, so it's important to separate out your journal publications into a different section on your CV, and you'll certainly be asked questions about this.

My letter writers for the Israeli market were not the same as my letter writers for the US CS market. I was told that seniority is much more important in the Israeli market, as opposed to perhaps the person who knows you and your work the best and thinks the highest of you, even if they're more junior, so I only used my most senior letter writers. In Israel, I emailed my contacts before applying and asked about the process, whereas everywhere else I just emailed my contacts after submitting my applications.

Plus, for any market that's different from where you are currently, you're sure to be asked why you want to join. Why do you want to move to Israel? Why do you want to be in an OR department? And you better have a good reason, because no one wants to give away their precious slots to someone who doesn't really want to be there. For example: My work is interdisciplinary, but I don't have as much experience with the applied, so I'd love to be in an OR department to have more applied collaborators with their connections to be able to get my research more connected to practice. And, I'd love to live in Israel because all of the time I've spent there has been some of my happiest, plus it's a million times easier to implement allocation systems with the government, and it's the greatest academic hub of all, even more so than New York or Boston or the Bay area.

Where to Apply and Getting Organized

Pretty much all CS-related faculty positions are posted on the CRA job page, and the best thing to do is to subscribe to the email list by filling out the right side of that website, and then take note of the relevant job ads as they come in. Sometimes there are more specific aggregations, e.g., CS theory jobs. For operations research and industrial engineering departments, many posted on the CRA job page regardless, but I also specifically went looking for postings at the schools that have more engineering departments (compared to business schools). For me, these schools are: Cornell ORIE, Georgia Tech ISyE, Stanford MS&E, Columbia IEOR, Northwestern IEMS, Michigan IEOR, and in Israel, Technion IE&M.Another great resource is the "Future Faculty Forum" slack channel created by Supreeth Shastri. To join, email him at supreeth-shastri@uiowa.edu. This is a closed community only of this year's academic candidates formed to help each other out gathering job listings and answering one another's questions as they go through the job market experience together. Sometimes sub-communities form as well—for example, I was in a 9-person "2021-israel" channel that I found extremely valuable for candidates searching in Israel.

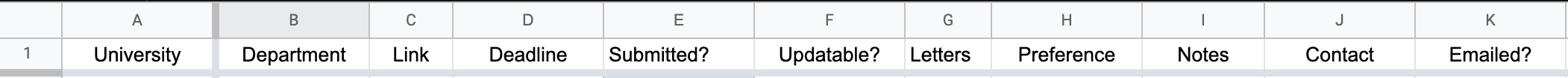

As for choosing from the list of schools that have postings. The first thing to note is that if a posting lists a preferred area within a larger posting, even if that's not your area, you can apply anyway. However, if the posting specifically says "Assistant Professor of Computational Neuroscience" and is entirely geared toward that, then you really need to be a computational neuroscientist. Otherwise, I think my list narrowed naturally. I think in my head, I was considering location, quality of students at the school, known colleagues within and outside of the department, etc, and if something fell too low in various categories then it got nixed. I wound up making a spreadsheet with the following columns: University, Department, Link [to application], Deadline [for application], Submitted?, Updatable?, Letters, Preference, Notes, Contact, Emailed?.

- "Updatable" was something that came up later—after I found embarrassing typos in my cover letter, or wanted to add something to my CV, or whatever. Some of the applications are updatable, and if so, note it and save the link as to where you can update!

- "Preference" was not a total-ordering of the schools or anything. It was a rough sorting of the various positions into tiers. I think there were about 6 schools ranked "1" and 0 schools ranked "3" if this gives you an idea of the coarseness.

- "Notes" was where I noted what was different about this application or process. E.g., one school wanted a "service statement."

- "Contact" was someone in my subfield, preferably who I already knew, who I could email after having submitted my application so they could make sure it didn't fall through the cracks.

- "Letters" contained information about how many letters of recommendation the school requested, whether they asked for the letters directly or just names of letter writers, links to check on the uploaded letters (these links are extremely important!!), etc.

Recommendation Letters

Start thinking/asking mid-September. As late as mid-late October will work for CS, though.Choosing: Start thinking/asking mid-September. Applications will give you the ability to submit 3-5 letters typically, possibly up to 7 if they're really unconstrained. Sometimes they really only allow 3, so when you're deciding who to ask, you should have a ranking in mind, "Who will be my top 3, top 4, 5?" and so forth for when you're constrained. You must provide a letter from your PhD advisor or it will look weird. I was told you don't need to provide a letter from your postdoc host, although 2-3 Israeli schools did specifically require it. I think a combination of how known the writer is and how strong what they can say about you is what's important. For your first junior faculty position in the markets I applied in, you don't need a letter from someone you haven't worked with—that's more like a tenure letter, and while it can be a strong thing to have if there's a famous person out there who loves your work and hasn't worked with you, it's definitely not a requirement for this search. Using all collaborators is great. But discuss your choices with your advisor.

Asking: Give your writer an out when you ask. All recommendation letters are positive, but not all recommendation letters are equal. Someone who did well in classes and has nice papers is not the same as the strongest researcher seen in years with real vision and who takes initiative. These are all positive traits, but of very different strength. So, you want to ask if your writer can write a strong letter, or give them an out for if they can't, because you don't want that weak letter.

Managing: Even if you apply to the low end of schools and have the low end of recommenders, it's still a crazy amount to manage to make sure all of the letters get in, especially since not every recommender is writing a letter for every school, and each letter goes to a different location. I made a separate google doc for each letter writer that contained a list of schools they needed to send a letter for, the deadline, what status the school was (not requested, requested, submitted), and a link to where they were supposed to submit or information about what email to look for or send to. This made it very easy to keep track of and remind my letter writers. Some never updated their sheets and I had to update for them; some did. Also, you of course need to remind your letter writers as deadlines approach, because they have a million other things on their mind. You're not annoying them if you remind them once in a while—it's helpful to them for you to act as a reminder (unless they tell you otherwise).

Application Materials

For Israel or OR, start really working on these by mid-late September. For CS, start really working on these by mid-late October.One of the most important things I was told is that there's a point after which it's not worth tuning your statements anymore. They're good enough, and you're wasting your time, so just stop. I think 2-3 weeks of full-time focus (application materials are your main objective throughout the day, even if your doing some other things) should be plenty, and any longer will drive you insane.

Going back to the principle of "what would I do on the other side?"—how would you judge an applicant? Would you care that much about their CV or the descriptions on page 4 of their research statement? Would you care at all about the specific LaTeX template they used? You'd probably mostly care about what their letter writers say, read the introduction of their research statement closely to see what their field is, how much it excites you, and what their contribution is, and at most skim other materials. So create your materials with this in mind! This is why there's a "good enough" threshold, because really you can express your field and contributions clearly, and it's up to your letter writers to do the rest. Here are some tips I've heard:

- The length of your research statement should be 3-5 pages. Don't go overboard. Make sure the introduction/first page of your research statement is incredibly solid. This is the most important part. It should make your area exciting, mention your contributions, and be easy to skim. There should be an easy sentence take-away for the committee of who you are that they can take to everyone else to convince them to interview you. The rest of your statement should describe your work so far and your future work, but the whole thing should be forward-focused, because what they're looking for is research vision.

- If you have trouble writing strongly about your work, think about it as writing about how cool your field is instead, and explaining that to people who don't know about it, and then just adding that you've made major contributions to it.

- Teaching statements should contain teaching philosophy, course plans, experience, and thoughts on advising. They should be at most 2 pages.

- Diversity statements should talk about your diversity and inclusion work and thoughts. They should be at most 2 pages. (These are not a thing in Israel.)

- research statement

- teaching statement

- diversity statement

- CV (at application time)

- cover letter

US Example—sent November 20 immediately after submitting application:

Subject: Applied to Y

Hi X,

I just wanted to let you know that I just submitted a faculty application to Y.

Hope you're doing (as) well (as possible)!

Best,

Kira

I also emailed in Israel, and I actually sent those emails earlier in the process. Some of the processes are a bit weirder in Israel—for example, Weizmann does not do interviews. You can arrange a seminar talk through a contact, but that's it. Or, at least last year, one of the schools didn't post how to apply until super late, and the only reason my application got in on time is because it was sent through my contact.

Israel example—sent October 15 before applying at all:

Subject: Applying to Y

Hi X,

I hope you're managing during these crazy times, and enjoying getting out of the house after the latest lockdown!

I'm writing because I'm applying for faculty positions this year and I'm planning to apply to Y. I was wondering if you have any insight about the process or other information that you could share with me.

Thanks!

Kira

P.S. My department is hiring!

Part II

November 19, 2021

As promised, my next installment on the ever-fun-to-talk-about job market! Here's what has come up from conversations with people on this year's market, as well as thinking back to the next events in the sequence.

Screening Calls

Many departments now have "screening calls" for their ~top ten applicants before the determine the top ~3 to interview for a position. This is extremely prevalent in OR, but also in Computer Science these days. I want to remind you that I was on the market during peak pandemic, so I have no idea how representative this is, but here's what I observed. No CS programs in Israel had screening calls. Every OR program I applied to had a screening call. Of the North-American CS interview invitations I received, 28% had screening calls beforehand, and the rest of the invitations came directly.The calls have some number of interviewers, possibly ranging from 1-6 people, could be via zoom or phone, and were almost always around 30 minutes for me. Often times, I was given the format in advance to prepare for, for example:

- Give a 5 minute overview of your research accomplishments (without slides).

- Give a 5 minute overview of your ongoing and future research goals.

- 5 minutes for the interviewers to ask clarifying questions.

- 5 minutes on why you're a good fit for X university.

- 5 minutes for you to ask questions.

Here's what I looked up before my screening calls to prepare:

- who my interviewers were (assuming I was told)

- what courses I could teach in this specific department (especially relevant for e.g. OR and data science departments, and to know which classes would be taken by existing faculty)

- features I liked about the department, most natural collaborators, some more stretch interdisciplinary collaborators

Some other advice on preparing for screening calls by Baris Kasikci and Shomir Wilson. Edit May 2023: Roei Tell recently wrote a post-mortem on his job market experience, and includes (among many other valuable things!) an appendix on questions he was asked.

Scheduling Interviews

My main insight here is that it takes at least a day to recover from an interview, if not two. A day with nothing on your calendar. A day to sit at home binging netflix (or working out, reading a book, whatever you fancy) while you slowly muster up the strength to email out thank you notes. Do not schedule back-to-back interviews, even if it seems convenient for your travel plans. You shouldn't be doing more than two interviews a week, really, but if you have to squeeze in three one-day interviews all in the same geographic region, at least have a day off in between.How? They're pressuring you and ignoring your requests? Well, right now they might be forcing you to pack them in, but in a week or two, your calendar is actually going to be entirely packed. So don't use flights or preferences as an excuse, just say something like, "Unfortunately, my calendar is already packed. I am first available the week of X, on the days of the Y and Z." I promise, your calendar will be full soon, so it's worth it to plant your feet and get the right dates now.

Also, you want your top choice school(s) to be ~3rd or 4th in your line-up. Your first interview or two is going to be a little rough while you smooth out the kinks. Your tenth or fifteenth interview is not going to register to you, as you move through it as a shell of a human. So, somewhere in the middle is ideal.

Some schools ask you for input on your schedule. I usually asked for student-meetings (a meeting with a group of PhD students), possibly named some specific faculty I was interested in meeting with, and mentioned that I was generally interested in meeting with folks who did interdisciplinary research with policy or healthcare. I also had some requests more pertinent to zoom interviews.

Zoom Interview Tips

This section is just for those of you who might still be having interviews over zoom. None of my interviews were in person (except for back on my postdoc market), so I can't help there.Talk Setup: To give the same energy as during a typical in-person talk, I stood during my zoom talks. I used a monitor in addition to my laptop, and moved them over to a counter so that they were at the appropriate height. I also bought a razer kiyo webcam to improve on the built-in webcam of my laptop, and it comes with its own very basic ring-light. Then when presenting my powerpoint, I put the presenter mode on my larger monitor, and the display screen on my laptop. I used boxes to prop up my laptop behind and above my monitor, so I had it just above. Then I would share just the display screen of powerpoint in zoom (start presenting in powerpoint, command-tab over to zoom, share screen and just share that window that now exists). Now, pop out your chat and participant windows in zoom and drag them over to your monitor window covering spots you don't need, so you can see questions in the chat and hands being raised. And I would resize the videos on my laptop window into gallery mode and to fill the whole laptop screen. This way, I was using my monitor to present my talk and to monitor participation, and glancing up at my laptop (just above the webcam, so looking at the camera) to look at people's faces. I used a bluetooth keyboard to advance slides and a bluetooth mouse as a pointer. I used bluetooth headphones as both headphones and a microphone. I found this set-up incredibly effective. I also literally moved my monitor/laptop/keyboard/mouse to the counter and back to my desk before and after my talk every single interview. (A standing desk would make things easier, I'm sure.)

Breaks: During in-person interviews, breaks occur naturally as people walk you from meeting to meeting, or you stop at the restroom between meetings. During virtual interviews, they don't. No one thinks about the other meetings you have. Everyone logs on exactly at :00 and off exactly at :30. Some places were nice enough to end meetings at :25 or start meetings at :05 on the schedule, but most faculty didn't actually notice and still held them for the full 30 minutes. So when asked what you want in your schedule, ask for 5 minute breaks between meetings. You'll need them—to breathe, to run to the restroom, for coffee, and because you won't get 80% of them.

Meal-and-Coffee-Prep: My understanding is that for in-person interviews, you get taken to breakfast, lunch, and dinner, and these meetings are part of your interview. You get 1-2 hour meals where you chat with people. And maybe this is a bit stressful, but you get a nice relaxing meal. During every single zoom interview that I had, I got at most a 30 minute break for lunch, no lunch or delivery gift-certificate provided, and then back to a packed day of meetings. So, you're not exactly cooking or going out to grab food during your 30 minute lunch break, especially since your meeting before will surely run over, and you haven't gone to the restroom in hours. I always made my food the night before (or more realistically, ordered-in the night before) and just heated up so I could spend the short time eating. I also prepped multiple cups of coffee in the morning so that I could quickly run and grab some ready-to-go coffee during my two seconds between a zoom call that maybe would occur, since people aren't walking you around hallways offering to get coffee with you.

Notes: While it might be a bit odd to take out a notebook and scribble down notes in the middle of an in-person interview, it's not even noticeable when someone takes notes during a zoom interview. I kept a document open on half of my screen with my interview schedule and information on the people I was meeting that I looked up ahead of time (e.g., what kind of research this person does), and took light notes about our conversation. The conversations totally blend together after, so it's a nice reminder about your impressions of the school, is useful for thank-you notes, and wound up giving me a lot of great research ideas. (When else do you get to just get zillions of outside perspectives on your research?)

The Job Talk

This is arguably the most important material you can prepare in the whole job market process. Here's how my preparation went. I spent about two weeks working on my talk full-time, doing nothing else. Then I started presenting parts of it to my PhD advisor, postdoc host, and junior faculty friends. Every time, I was essentially told to remake the entire talk, and to make it 1/4 as technical. This happened over and over until I'd remade the talk entirely and, in my opinion, the talk was completely non-technical.Now, let's look at it from the other side. The faculty are seeing 4+ interviews for every position they're hiring, in addition to their busy jobs, of course. They just want to know if you work on cool stuff, are a good researcher, and will be a good colleague. But they're tired. Would you want to have to have laser-focus on a semi-technical talk out of your area to assess these things? Or would you rather learn something new and cool by being spoon-fed some nice explanations?

My job talk took the following structure:

- introduction about my research area and how I've contributed

- what I'm going to talk about today

- main "technical" research content

- healthcare: problem motivation, model description, description of result, why that's interesting

- carbon markets: problem motivation, model description, description of result, why that's interesting

- online labor markets/gains from trade: basic model and objective, what optimal would look like, basic classical results in this model, our approach idea, illustration of our algorithm/mechanism (via english and animation, not math or pseudocode), description of results and why that's interesting

- overview of some other areas/results of mine

- other areas/problems I'm thinking about going forward

Oh, and when you're practicing and getting feedback and remaking your talk a zillion times in the beginning? Don't overweight each individual piece of feedback. Try to understand the essence of what people are saying, and take it from there. For example, the more senior faculty told me to order my content in exactly the opposite order as the more junior faculty that I got feedback from. Needless to say, it's okay not to follow every single piece of advice.

Here's some good general advice I got (and followed):

- Make it less technical, no less technical than that, LESS TECHNICAL!

- Don't use variables or jargon whenever possible. Illustrate with examples and real numbers. E.g., "the patient is willing to pay $10 for the service" instead of "the bidder values the item at v."

- Put your most technical content last (within the core content). That way, most people are already sold after the interesting high-level content, can decide they're hiring you, and can doze off or check their phones, and only the remaining relevant people need to stay focused.

- Always tell people what's coming next. For the full talk, within each section, within a slide ("we're going to use this to try to prove X"), etc.

- Write out an approximate script for the introduction.*

Also, for full-disclosure, I had a hype-up song that I listened to right before my talk. My process was: listen to transition recordings, relax, then listen to my hype-up song. Highly recommend.

One-on-One Interviews

As I touched on a bit under "notes" in the zoom section, one-on-one meetings can be really fun. There's basically no other time when everyone is so focused on you and your research, and you get to just hear people's perspectives and get cool ideas. It's actually quite inspiring, and I recommend trying to keep track of the cool research ideas that come up.Now, remember, the people on your schedule are trying to evaluate if they want you in their department. That is, do you do cool research, fill some void/need of theirs, and would you be a good colleague? For the most part, the first two questions are answered by your job talk and application. The one-on-ones are for the super-engaged to dig deeper, and for anyone to evaluate if you'd be a good colleague. A lot of people just sign up to be on your schedule to "help out," because they want to give you a good interview experience. But they're busy, so they didn't pay attention to your talk or prep for your meeting. And then it's time for your meeting and they don't know what to say. So they go ahead and say the infamous,

"Well, people have probably been asking you questions all day, so let's see, do you have any questions for me?"

Now, it's your 10th one-on-one of the day and you've asked every question you could possibly think of 10 times already, and you know more about their university than they do at this point. So what do you do? You have 30 entire minutes to fill. To me, this was the worst kind of meeting.

The worst kind of meeting is not someone grilling you as if there's a flaw in your research. You are extremely prepared to defend your research. I had maybe 3-4 meetings where I was grilled like that total in all of my interviews combined, and it only lasted 2-10 minutes in each of those meetings. The first type of meeting is much more common. So the best thing you can do to prepare is have a million different types of questions to ask, and have that list in front of you (or committed to memory).

Questions to ask:

- What is the typical teaching load?

- How courses are assigned to faculty? Are junior faculty given courses that will help them recruit PhD students, or at least given a transition into teaching?

- How do new faculty get mentorship? Is there some official mentorship program?

- What happens if at some point you don't have grant money?

- What are the first few years typically like?

- What?s the tenure process like—is it stressful?

- What is the department's planned trajectory over the next five years?

- How do PhD admissions work?

- How is the department's administrative support? How painful is it to submit grants/how much do the admins help?

- Do the junior faculty hang out/socialize with each other?

- Do they have faculty friends across the university (outside of the department)? How did they meet them?

- What is a typical service load? How do service assignments work?

- What is the department's atmosphere like? Do people chat with each other in the hallways? Do faculty collaborate together? Across research areas?

- Where do most faculty live?

- And my favorite: What do you think I'm forgetting to ask that I should be asking?

Student Meeting: Now, the meeting with PhD students is a very different kind of meeting. Students are the most open people you'll meet, so this is the meeting where you should look to extract whatever everyone else might be dancing around. Some universities are known to be going through things... faculty moving away, having some jerk on the faculty, some scandal in the news, whatever else, but this would be awkward to bring up in your one-on-ones. The student meeting is the place to try and bring that up. In the student meeting, I usually tried to assess how happy the students were, and how much initiative they were taking without faculty. I'd ask questions like, "Do you run any reading groups without faculty? Do you have any collaborations with other students that the students initiated?" I might also ask, "Do you feel like you have a life outside of work? Do you think your faculty do? How stressful does it feel in the lab around deadlines?"

I had a conversation with a friend the other day who was asking me just how direct one can be with their questions during interviews. They asked, "Can I say, are people nice? Can I say, are your students good?" I said, no, but you can say, "Do people chat with each other in the hallways? Do they go to lunch together? Are the faculty friends with each other?" And you can say, "What schools do you compete with for PhD students?" Whatever you want to ask, there's probably a way to phrase a different question that gets at the same information, and you just have to learn how this skill.

Thank you notes: There's a lot of debate about whether to send thank-you emails or not, and what they should look like. I don't think there's any harm to sending them. Mine were all identical except for one personalized, genuine sentence in each (and my notes from my meetings were helpful here). I tried to send them within ~3 days of the interview, usually the day after when I was decompressing by watching Bakeoff and writing thank you notes at the same time. The only time I didn't send thank you notes was after some interviews in Israel, because Israeli friends told me that it was really weird, although I had already sent some and seemed to get positive reactions, so whatever. Here's an example of a thank you note I sent:

Subject: X one-on-one meeting

Hi Y,

Thank you so much for taking the time to meet with me during my virtual visit to X on Monday. I really enjoyed getting to chat with you -- [I think your work on team formation and freelancing within labor markets is super interesting, and I also appreciated hearing about how you felt in the department as junior faculty.] I hope we get to chat again sometime soon!

Best,

Kira

The highlighted sentence is of course my "personalized sentence."

Part III

March 18, 2022

Here is the much-delayed final installment about my job market experience. For all on the market this year, I hope you are near the end, and that you can begin your much-needed rest and healing. As someone who is a year out, I can promise you that the healing will eventually come—your soul and energy will return. Okay, here we go.

After You Get Offers: Declining, Withdrawing, Extending

Timing is everything when you're on the market. Trying to get schools to line up across one market is hard enough, let alone across multiple markets. And then having time? Not really a thing. Once you have offers, you might want to free up your time with respect to interviews that you already have scheduled, and you might want to make sure you're not wasting any political capital with places that are clearly dominated.Deans and department chairs will completely understand. They do this every year. They are incredibly used to having candidates withdraw and decline during the process. 100% of them were incredibly nice to me and wished me luck, some even said other wonderful things. It seems terrifying to disappoint these people who have been working with you, but really, they were so great about it. And they want their time and resources back! They want to move on to other candidates. So go ahead and free up that time and those resources.

There are some people who might respond as being hurt or less understanding. Those are your contacts at the universities who are rooting for you to join. What it looks like from their perspective: they've been pitching your case to the hiring committee. They've been going around trying to convince everyone that you're a superstar and their department needs you. And they have their hopes up so high that they might get you as a future colleague, a new forever-friend to join them at their place of work every day. They're the person who might be hurt. Not the dean or department chair. So send them a nice email and be understanding/sensitive here, and make sure you thank them profusely for their time.

In terms of ending the process, and especially in declining an offer, I received very good advise to always cite a reason that is completely out of the university's control—location, two-body, whatever, but not something that they feel they could potentially change.

Withdrawing and canceling an interview:

Hi [Chair],

I hope you're doing well! I wanted to update you about my search status. I've received several offers—from [list]. I'm very excited about these places, and after a great deal of thought, I've come to the conclusion that it's much more likely that I'll accept one of these offers, so I think perhaps it makes the most sense to save [University] the effort and resources of putting together my interview. I know the talk details have already been posted online, so I'm happy to still give the talk if that's easier—let me know what you think is best.

All the best,

Kira

Declining an offer:

Hi [Dean],

Thank you so much for all your help throughout the interview process. I am now a bit further into my decision-making process, and while I'm certain that [University] would be an exceptional academic fit, it has become clear to me that living in a city is more important to my productivity and happiness at this stage in my life than I had previously realized.

I had a really great time during my interview, and I'm truly appreciative and very honored to have received an offer from [Department]. I'm sad not to get to know the faculty and students at [University] better—you have a wonderful school with both excellent research and remarkable community.

All the best and thank you again,

Kira

Extending an offer:

This is probably the only section in this whole post that I feel I was slightly strategic or deceptive about, and only barely. What's important here is that it takes a long time to formalize and write down an offer. Given that offers are powerful things that can help extract offers or better parameters from other schools, it might seem like you want to get a written offer as fast as possible. Most people will probably tell you this. That's not the principle that I operated on. Written offers come with deadlines, and I did not want deadlines. So my approach was to happily take my informal verbal offers and delay/draw-out the formal offer process.

For example, on February 1, one school let me know that I had been approved for an offer, and that they would need an equipment budget from me and a predicted deadline in order to put together my written offer. Now, partially because I was in the midst of other interviews, and partially because I had no idea how to put together such a budget and had emailed other faculty for examples who hadn't responded, but also nonetheless partially to draw out the process, 10 days later I received an email from the dean asking me for my progress. We exchanged some emails back and forth where I explained that I was confused about the budget. We decided to have a zoom call. By the time we scheduled and actually had our zoom call, it was February 17. I received my formal offer on the 18th. Given that deadlines are often 2-4 weeks, those extra 18 days were huge.

For another school, I was actually warned that they give extremely short deadlines, and that they make offers immediately after the interview, so when it came time to schedule my interview, I was insistent on scheduling the interview late. Go back and reread the section on scheduling interviews if you still feel uncertain about insisting on certain times for your interviews.

For yet another school, they told me it would take them a while to go through the process, and I myself was already well into the process due to the multiple markets when they invited me, so I asked them to schedule my interview literally as soon as possible. I think I wound up having my interview within a week of my invitation, but as a result, my offer synced up with the rest of my offers, so I could actually consider it.

Another way that I extended deadlines was just by being genuine and explaining what was going on with me and why I was asking for what I was asking for. You might notice this as a recurring theme. Par example, here was my heartfelt plea for more time (which was granted):

Dear [Dean],

I wanted to update you on where I am in my faculty search and decision process: still extremely interested in [University], but not yet ready to decide. I know that my written offer letter has a deadline of [Date] in it. As you know, the American faculty market is much later than the Israeli market, with interviews typically bleeding into May. I've managed to contain all of my interviews to March. I have offers from [list], and have already begun turning down and withdrawing from other schools (as I did everywhere in Israel aside from [University]).

At this point, in order to make my decision, what I really need is for my interview process to conclude so that I have some more time on my hands... and then to use that time to talk to many people and think over what to me is obviously a huge life decision of moving to Israel. I love [University] and I love [City], I just need to gather a lot more information about what my future of living in Israel long term would look like before I can commit to this major change for me.

So, I'd like to ask for more time to make the decision, and a good bit of more time—another month, until [Date + 1 Month]. I know this is highly atypical for Israeli CS offers, but then again, so is a non-Israeli applying for faculty jobs in Israel, so I hope you (plural—I know this is not only your decision) will be understanding.

All the best,

Kira

Second-visits

As my experience was during peak covid, I had no in-person interviews or second-visits. Most places didn't mention second-visits at all, but one or two had virtual second-visits. These consisted of zoom calls with people further afield to see who else I might collaborate with if I chose this university and learn about how interdisciplinary relations worked across departments, plus to establish potential secondary (0%) appointments.I did, however, ask for three minimal in-person second-visits. They were essentially just enough time to walk around the campus and see the buildings with 1-3 people from the university, not to have a full visit. However, I learned extremely valuable information. For example, I learned about where people sat. One university had the CS department split across three different far-apart buildings and was planning to seat me far from my closest collaborators. At various universities, I learned whether departments sit together in one building or are split across multiple, and whether those buildings are close together to each other or not. I learned whether students sit in 3-person offices or 30-person offices. I learned whether faculty offices were clustered near each other on 2 floors, or whether they were scattered seemingly randomly across 5 floors. I found this very informative, and even determined that where I sat at one university was the most important factor to me.

Of course, there are other things to learn, like where the good food spots, how "good" those food spots are, whether your future colleagues find drip coffee acceptable or nespresso or insist on a $10,000 coffee machine that looks like a spaceship (as they should). Typically people drive around and look at various potential neighborhoods to live in, learn about the housing market, etc. Anyway, I'm not the expert here because again, covid, but I'm someone who is vibey and cares a lot about how it feels to be in my work building daily and how it feels to run into colleagues, so even these mini-visits were important to me.

Negotiating

These are the main parameters that I tracked for varying with some examples that demonstrate the various forms they come in. They vary a lot across universities and departments and are definitely not the same across the board.- Salary: For example, 120k over 9 months. This means that you're guaranteed 120k every year by the university ("hard money"), and you theoretically can pay yourself approximately 3 months during the summer out of grant money at a rate of salary/9 (e.g. 13.33k per month). However, summer funding is very difficult to find. NSF grants typically allow a maximum of one summer month per grant, and you can only fund yourself with a maximum of two NSF months per summer (even from different grants), so you'd also need industry gift funds or start-up to cover the third month. Assume that you're getting 11 months a year, so 11 (13.33k) = 146.63k (or whatever your rate is). What this means logistically is that you'll have 120k/12 = 10k (minus taxes and other deductions, so more like 7k) paid every month 12 months a year, and then whenever you pay yourself a summer month, that month you get the 13.33k (but after taxes/deductions) paid on top of the typical 7k. My lowest initial offer was 110k and highest initial offer was 135k (both over 9 months).

- Summer Months: For example, 4 months, at most 2 months from start-up per year. Since you need to pay yourself in the summer, your start-up typically comes with ~4 months to get you off the ground.

- RA Years: For example, 4 full years (includes summer). Things to note or ask: is there any recurring/departmental funding for students/RAs? What if you at some point run out of funding—is there a safety net of funding in that case? What if you're advising/working with students in other departments, can your start-up funds be spent on them? (Be delicate about how you ask this question.)

- Discretionary: For example, 50k. This means "bucket of money for literally anything else." Travel, equipment, seminars, bringing visitors, whatever.

- Teaching Load: For example, 1-1 with every 4th class a topics class. Or in English, one class per semester, where one is undergraduate/masters level for a semester, and the other is PhD level for the other semester, and every fourth class you teach is a PhD-level advanced topics course on whatever you'd like to teach. Be sure to ask how teaching assignments are done.

- Teaching Release: For example, 1 any time pre-tenure. Or 1 in the first year. Or 1 every 3.5 years. This is a pass to take the semester off teaching, but often comes with restrictions about when you can use it. You want to use this to do course development if you're teaching new courses, or to take the semester to go travel to some cool research initiative being held elsewhere. If you're someone who likes to do this a lot (e.g., to go visit the Simons Institute or MSRI), it's good to ask if can do something like teach 2-0 instead sometimes.

- Moving: For example, up to 10k but reimbursable only. Or 10k lump-sum. Or 10k and rolls over to your start-up budget.

- Computational: For example, 70k for cloud computing. Or 50k that the department will match if you use it to contribute toward shared cluster resources.

- Equipment: For example, 25k to buy yourself and your students computers, iPads, etc.

- Expiration of start-up funds: For example, technically the package expires in 3 years, but this doesn't really happen and the department has no way to revoke the funds.

- How many summer months does the university allow you to pay? While it's typically 3 months, one university I talked to only allowed you to pay a max of 2.5 months (e.g. 2 weeks forced unpaid every year), and one university had a strange model of 8 academic months, 4 summer months, but only 3.2 of those summer months could be paid. I don't know where these numbers come from, but it's good to know in advance, and it impacts your maximum and average annual salary.

- Can you transfer money between buckets? Often times the buckets are separated out because they don't want the money to be transferred, so it's immovable. Sometimes the buckets are just suggestions, and you can change the money around either in negotiation, or even after the fact. That means if you don't get students, you can wind up using that money to pay yourself, or if you over-yield students, you can use your computational money on them instead (for example).

- How much overhead does the university take for for grants? For gift funds? I saw overhead range from 55-65%, and I saw gift fund overhead (like industry grants) around 15%.

- How much does a student cost? For example, 40k for just salary and fringe (so this is how much you pay when paying out of start-up), 75k with overheard on top of that, and 10.23k for tuition per year. Note that student salaries, fringe, overhead, and whether faculty need to pay for student tuition varies highly across universities.

- How much does a postdoc cost? As their employer, you pick the salary, say 80k. Then for example, if fringe is 26.5% and overhead is 65%, then a postdoc will run you 101.2k per year from start-up (without overheard) or 166.98k per year from grants.

- Where will my office be? What sort of office space will my students have and who controls it?

- Is relocation covered?

- How do retirement benefits work?

- Are there any transit benefits? For example, a metro pass with pre-tax dollars or subsidized? Bike reimbursement? Parking benefits?

- Are there any childcare benefits? Most places told me "we have a university childcare, but it's impossible to get into, and there are no discounts."

- Are there any tuition remission benefits? This is for if you want to have a dependent attend college. For example, free if they attend your university, nothing if elsewhere. Or, half-tuition if elsewhere. Note that I asked this even though I am far from being in this position.

- How do raises work? (How frequent are merit raises, or is it just cost-of-living adjustments?)

- How's the university gym, is it accessible to faculty, do they use it?

- How's healthcare?

- Is there any support for a down payment on a house? Most places only give such a thing to senior faculty, but some places have such a thing (like MIT).

- What benefits are there for relocating one's partner? This is actually negotiable. I know someone who negotiated 100k for their partner to do a masters at any school.

Salary is incredibly difficult to move. For one place, I had another offer with a salary that was 25k higher, so they immediately raised me 5k and told me that was the maximum that they could do—it was clear that they had a pre-approved range for negotiation with a hard max. At another place, I asked to increase the salary by 1.5k and they had to take this request to the provost and assured me there was no way that would happen, that's how hard it can be to move salary. This is not like negotiating salary in the tech industry.

On the other hand, when it comes to your start-up package, almost anything is on the table. The most important thing I learned is that you need to explain why you want things. Universities have a lot of really weird rules going on behind the scenes (which probably explains all of the bizarre things happening to you in this process). At one university, I told them many times that I wanted more money in my discretionary budget, and that another university had given me 70k more in discretionary money. They told me they couldn't increase my discretionary budget, period. Then I explained that (1) I was really excited about organizing workshops and seminars across the geographic area, (2) international collaboration is really important to me and I was hoping to bring scholars to visit and send myself or my students to visit, and (3) I suffer from chronic migraines, so I need to be able to purchase some additional (and expensive) equipment like e-ink monitors and tablets. Suddenly, I had everything I wanted—a separate pot of money to host workshops and seminars, a separate pot of money for equipment so that I didn't have to pay for equipment out of discretionary, and the difference left in my discretionary would cover the international visits. This is where being on the same side comes in—by explaining why I wanted various resources, how they would help advance my career, the department was completely behind me. There was no strategic hardball against each other. Which is nice, cause I'm not that kind of person, and I didn't have to be. I just had to ask for what I wanted and explain why.

Decisions

I can only say what my decision was based on. I was primarily optimizing for day-to-day happiness, so I asked a lot of questions about whether people seem happy, what they do for fun outside of work and family, etc.This meant that a large factor in my decision was location. I chose Boston because (1) it's an academic hub with many many universities close together (~15 minutes apart, not an hour apart) as well as research labs. This is advantageous not just collaboration-wise, but also socially for those of us whose social lives are now way too embedded into academia, both because friends will live nearby and because friends will pass through frequently for academic reasons. Boston's a focus city for Delta and is served by Amtrak, so there's lots of easy travel. And (2) I grew up in Philadelphia, so my family isn't too far and people I've known from childhood and undergrad have settled in Boston, giving me non-academic friends in the area (a crazy concept!).

A second huge part of my decision was environment. It is really really important to me that people are friendly where I am, that people talk to each other even if their research areas are far apart, say hi in the hallways, and that it doesn't feel like there's much hierarchy. I like it when students feel they can be less formal with faculty, when systems students are friends with theory students, and so forth. And as part of this, I want to be part of a group of good people who I feel embody this, who I want to see in the hallway.

The third main thing was placing myself in a place that would best motivate me to do the type of research that I want to do. To me, I felt that at the end of the day, this really came down to people, not the types of funding or initiatives in my start-up. There were certain places where I felt I'd have a million fantastic collaborators, but I feared I'd stick too much to the type of work I've been doing that's more "classical," rather than exploring more into new directions that I'm excited about. On the other hand, other schools I thought would encourage the new directions, but didn't offer me any close collaborators. I wound up choosing a school that I thought offered me a good balance of researchers not too far from my methods and people further afield to inspire me to work in new directions.

These were the three big things that impacted my decision. Here are some other things that also had some impact. Offer package, of course. Where people sit—is everyone together in one building, or is the department split up across spaces? How easy or difficult is it to get students (and where does the school compete with)? Are they planning to continue hiring, and if so, will they hire more in your area? What sort of course development or service requirements will be expected of you? How much will you be listened to if you want to contribute to shaping things? How are the benefits? If, for some very unfortunate reason, you are unhappy, how easy would it be to move from there?

Blog home »

Part IV: Perspective from Current Faculty

Nov 19, 2024

Halfway through my fourth year as faculty, I thought I'd write one more part to share some job-market-related things I've learned from the "other side." I've been on the search committee two of the past three years, and involved with hiring in some way every year, both in my department and others. TL;DR: No one is out to get you. For anything not going your way, it's probably due to people being busy or bureaucracy. And there are probably people working very hard for you behind the scenes regardless.

Principle 1: Randomness

People will tell you that the job market is random. People will tell you it's a crapshoot. It is. I think it's hard to get a grasp of quite how random it is, but let me try to paint a picture. It's not just the randomness of who you're competing with. Many universities have to submit proposals to the university or provost toward who they want to hire in the coming year at the beginning of the summer. This means, without knowing who will be on the market, without knowing who will be in that application pool, they must ask the university for, e.g., a Computer Vision line, an NLP line, and a Graphics line. They can blur the line a bit more by proposing general "usable AI" lines or "applied ML" or what-have-you, but if a highly unique candidate comes out of the blue and doesn't meet what they've gotten approved, they would have to go back and propose a new line on-the-spot to the provost. If it's clear that you're one-in-a-million, they may absolutely try to do this, but if the person reading your application isn't close enough to you to be able to tell that, they might just discard you as being too far from this year's lines.And let's talk about who's reading your application. I think I'd compare it to an NSF Panel or a broad conference. Sometimes you're lucky and the person with your application knows your area, or who you are, and will be able to give it a much better read. And that is definitely what every committee is optimizing for. But sometimes there's no one on the committee in a certain year who's like you, or sometimes that person just had too many other applications assigned, so you get assigned to someone else. Generally, your application first gets read by 1-3 people in the "triage" phase, and if there's not enough excitement (particularly because they don't know your area well enough to be excited by you), you may be cut. Past the triage stage, you get discussed by the full committee, so you have a better chance of getting an advocate, and it also means someone was already excited about you.

Principle 2: Individually, Occam's Razor: Faculty are Overloaded

It is extremely unlikely that someone is out to get you or is messing with you. I suppose it's possible that the things that happen against you could be because someone is optimizing on behalf of someone else. But for pretty much any example I can think of, the answer comes from Occam's Razor: faculty have too much on their plate, and things slip. Why didn't that person respond to your email? They're too busy, or they forgot, or it got buried in the other five bajillion emails they get. So they did email you, but it's super short and terse—are they mad? No, they're probably just trying to get their emails done as soon as possible (or they won't happen), so they're not thinking about receipt. Why did they mistake some feature about you with another candidate? It has nothing to do with either one of you. They're just trying to catch up on the various candidates, did so a little too quickly, and it got mixed up in their head. Why didn't they meet you during their interview, or why did they skip your talk? They were probably teaching, or advising, or one of the other too many things they have to do, or maybe the organizer just forgot to email them. I say this because since being faculty, whenever I hear some story about "something weird" someone did, I can 100% empathize and see it happening to myself.Principle 3: En Masse, Bureaucracy

Another thing I've heard people complain or wonder about is why it takes so long between various steps. If it's not principle 2 (e.g., getting faculty feedback on screening calls and it's taking forever because they're busy), then it's principle 3: bureaucracy at the university level is a lot. (Note that these are both what contribute to principle 1: randomness). So they interviewed you, you got positive feedback from individuals, but there's no word on an offer. Why not? Usually, the process looks something like the following. First, faculty discuss you in some capacity (feedback forms, emails, in-person faculty meetings). If feedback seems positive across the board, they may move to a vote. To have a vote, you either need to gather the faculty at a meeting (which can take some days to happen, you know, schedules), or you can run a vote electronically, which then needs to be held open for some number of days. When the vote concludes, assuming all goes well, the provost or other university-higher-up needs to then be briefed on the feedback, vote, etc, and be asked for approval on making an offer. Obviously it takes some time for the provost to get back on this. When the provost says yes, this is probably when you're given a verbal offer, but several more steps still need to occur before you can be given a written offer. And, typically offers are being made in parallel, but there's a limit to how many, so sometimes you're waiting for an offer to get declined from someone who just happened to interview earlier, even if they're not at all in the same area as you.A Comment about Your Allies

Lobbying to hire people is a hard job, and can become quite emotional, as I talked about in declining offers. From the faculty perspective: you think you might be getting a new colleague in your research area to forever collaborative with, co-advise with, run a lab with, etc. If something at your university makes it so you can't hire that person (even independent of that person's own preferences), it's disappointing! I write this because I often hear people say things like, "oh person X must not have really wanted me since I didn't get an offer there." If you make any headway at a school (screening call, interview), this implies that person X is your ally, already lobbying for you, and really wants to hire you, but wound up getting blocked by something else in their department or university, and they're probably even more disappointed about it than you are! So don't get mad at your allies who are already fighting battles for you behind the scenes, and just recognize that hiring is tough.Time Line from the Faculty Side

- End of May: Post-mortem on last year's faculty searched and proposal for next year's searches submitted

- Beginning of September: Areas/call for this year's searches finalized

- September and early October: Search and hiring committees built

- Application deadline

- ~1 month post-deadline: Applications read, screening (or direct interview) shortlist produced

- 1.5-2 months post-deadline: Screening interviews completed, feedback aggregated on screening interviews and interview shortlist produced

- Next 3+ months: Interviews scheduled. Feedback solicited immediately after interviews.

- ~Halfway through interviews, or later: Who to make offers to begins to be discussed.

Faculty View on Screening Calls

The main point of a screening call is to see if you match the person on paper. If you've been selected, it's because you've already impressed the committee. However, a candidate can (especially with assistance) hone documents over months, get good recommendation letters, etc, that don't accurately reflect who they are, so the screening call is more of a double-check: when you're alone and on the spot, are you that same person? There may also be a specific question the committee is trying to answer about your application, like: are you more theoretical or applied? Are you interested in interdisciplinary collaborations? It's also a way to solicit feedback outside of the search committee, so outside of who has already read your application and championed you.Faculty View on Interviews

After your interview is the first time we really all sit and give you feedback and discuss you. I think the three biggest things that are discussed are: (1) What do we think of your research? The senior people often steer this conversation forward-looking, like, "well they've done X so far, but I think in the future they're going to be crazy impactful," or, "they seem like the type of person who has a really interesting research agenda and then goes out and solves those problems." (2) What did we think of your talk? This lends itself to (1) as well, but also to your teaching and general communication skills, and how you might do at other parts of the job. (3) Do we think you'll be a good colleague? That is, did we enjoy chatting with you? Do we think you'll contribute well to the department?Why Offer Processes Differ

Some schools may be able to give you an offer right after your interview even if you're the first to go, whereas others may not be able to give you one until they finish interviewing most of their candidates. Some offers may have no deadline, while others explode in 2 weeks. This goes back to Principle 3: Bureaucracy. Some universities are large enough and have enough money that they're willing to take on the uncertainty in hiring and let it work like admissions, where departments can give out enough offers that the right number of people accept in expectation. Other universities do not allow more offers out than the actual number of lines, which means it's not feasible to give offers without deadlines, especially if the probability of acceptance is low, so offers often have deadlines of 2-4 weeks. Usually these are moveable if you are very interested (and thus have a higher probability of acceptance), but again, my point is that the department is not being adversarial, it's a result of university policy.Best of luck to all of you with your process and decisions! If hope you have some great choices and that you wind up somewhere where, most importantly, you can be happy. And I wish you a speedy recovery from this process!