Blog home »

Encouraging an Interactive Classroom

June 6, 2025

I've experimented with some methods in my classroom in the past few years, and this seems to have developed a highly-engaged classroom, both for myself and for others who have adapted them, so I thought I would share them more broadly, especially since as junior faculty we often jump into teaching without much guidance at all.

As an undergraduate TA at Oberlin College, I received training on how to engage and teach to a diverse classroom of different skill levels. The most important thing I got out of that training was being required to read this article: "Structure Matters: Twenty-One Teaching Strategies to Promote Student Engagement and Cultivate Classroom Equity", which while designed for a biology classroom, has strategies that work in any classroom and completely change the environment. The strategies I have found to be most influential using in my classroom are 1. Wait time and 13. Work in stations or small groups, as well as classroom norms:

5. Hand raising

10. Monitor student participation

11. Learn or have access to students' names

15. Be explicit about promoting access and equity for all students

17. Do not judge responses

18. Use praise with caution

19. Establish classroom community and norms

with more details on each one in the article, of course.

At the time, I sent the article to the professor I was TAing for, who started to implement some of the strategies, like longer wait time and "think pair share," and we both observed how the classroom came alive.

So, the strategies in this article have been my guide for everything else ever since, while TAing in grad school, and while developing approaches as a professor now. Even in sessions with the center for teaching and learning, I've mentioned this article and its massive impact on me and asked if there are any other or updated resources, and they say no, that's a fantastic article.

So here are the strategies I use to run my class, to maximize engagement. And I'll also outline where I'm struggling as education changes with the rise of LLMs, in case you have any ideas here too.

Interactive Worksheets

For teaching a mathematical class like algorithms or any other theory class, in my own experience as a student, I've always felt it best to have the math slowly written in front of you in order to learn. So when I started teaching algorithms, I decided to write each lecture on the chalkboard in my classroom. Three primary problems showed up.First, the board was hard to read. My board organization was terrible. There was only so much space. Even if I knew to keep the algorithm up, I'd erase other definitions. Colors would be difficult to see in the lighting. Even in the ideal classroom where everyone was close, there were still complaints.

Second, I had a hard time being precise. I would abbreviate things in my notes preparing for lecture, and then forget to write them in full rigor in certain places during the lecture, which would lead to a lot of confusion. As students also have trouble pinpointing what their questions are about sometimes, it took me some time to identify what the issue was.

Third, I would try to give in-class exercises like "come up with potential ideas for greedy algorithms for this problem," but they weren't well-defined enough, or the students would forget the exercise right after I said it.

As a result, I started developing interactive worksheets. What these worksheets are is essentially a carved out version of completed lecture notes, with the "answers" (proofs, etc) removed, big empty spaces created for attempting ideas or taking notes, and questions formulated in advance to help the understanding process. In addition, I have a filled-out lecture notes version as well.

I then post the worksheet before each class, and students print them out or bring them on their iPads. During lecture, I project the worksheet on my iPad. It is much easier for students to see the projected worksheet than a chalkboard or whiteboard, and it is much easier to use color options, etc. I can also post the handwritten notes from class afterwards. All of us, both me and the students, have the precise definitions already written out in front of us, so there is no confusion about definitions that are imprecise or accidentally erased. The in-class exercises are written out in advance as well, so when we pause for the students to work together, if they forget what they're working on, it's written right there in front of them, as are all of the previous components they might need to work on the exercise.

By developing these worksheets, it also forces me to think about interactivity when developing the lecture. I add intentional examples and questions that help students as they're first introduced to concepts and problems. It builds in the "allow students time to write" and "work in small groups" strategies from the article?by giving students time to work on problems alone or with others, they then feel more comfortable attempting to speak in front of the whole class.

During the in-class exercises, I walk around the classroom to see if students have questions. As you may have experienced, they often ask questions only when you're physically near them, so it really helps to walk around and give them that opportunity. It also helps you get to know the students better and understand how they approach the exercises. After giving students 5-10 minutes to attempt an exercise (and I really do watch the time, because it's really easy to cut time short when you're waiting for others to think?see the section on wait time), I then bring the attention back to the front and ask students for ideas (not answers!), try to elicit many different ideas, and prod them for full ideas, but not necessarily correct ones. I very carefully try not to give praise or show what the right answer is (as per the "do not judge answers" and "use praise with caution" sections), but in the end I actually try to praise everything for having good ideas that got us somewhere, to show that even wrong answers have good ideas and help us learn.

I typically do only 2-3 in-class exercises taking 5-10 minutes each per class. But, the whole lecture is sprinkled with questions that I may ask while lecturing, and I think having the question formulated and a blank space for ideas also encourages the students to participate, or even just remember what's being asked. The rest of the lecture, I just fill-in the open spaces on the worksheet with proofs or algorithms, but I try to take ideas from the class as much as possible to keep it interactive.

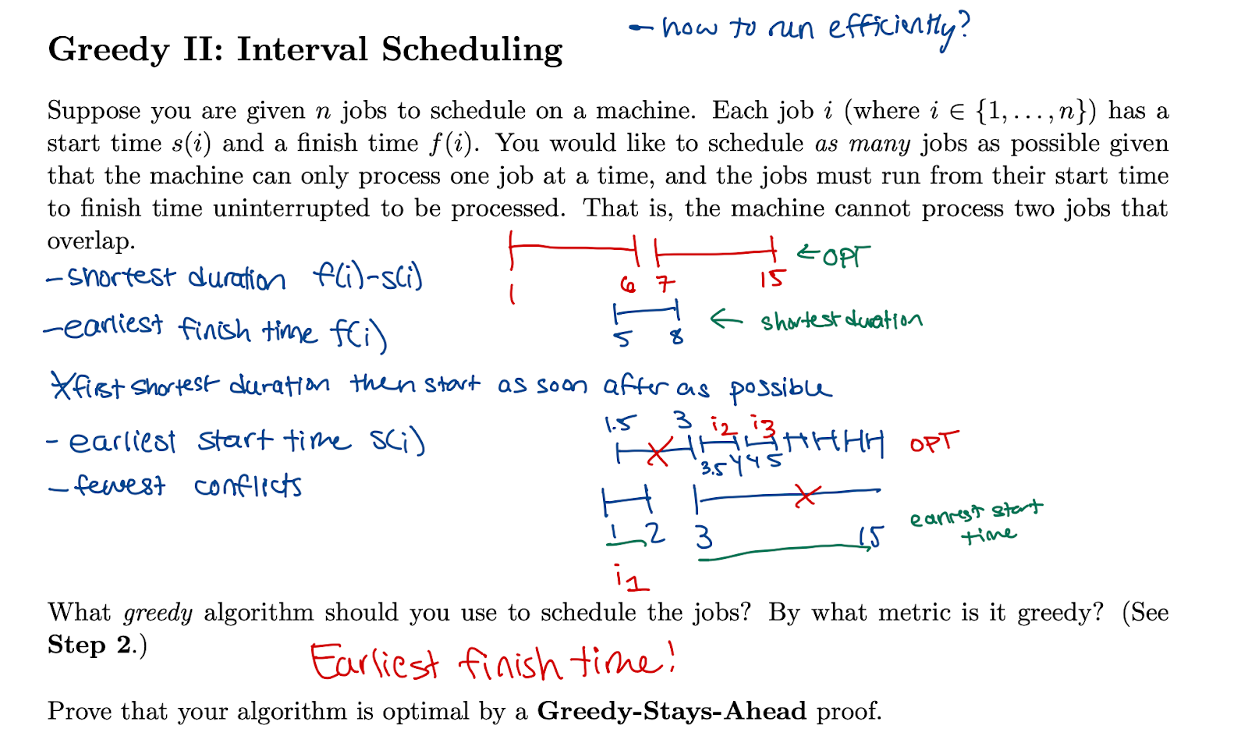

The above image is from my lecture on Interval Scheduling. Here, I give the students about 5 minutes to come up with greedy metrics for the problem, and I suggest they try and "break" (come up with a counterexample) for any metrics they think of as well. Then, together as a class, I collect as many ideas as possible, and then see if anyone has counterexamples for those ideas, until the only one left is the earliest finish time.

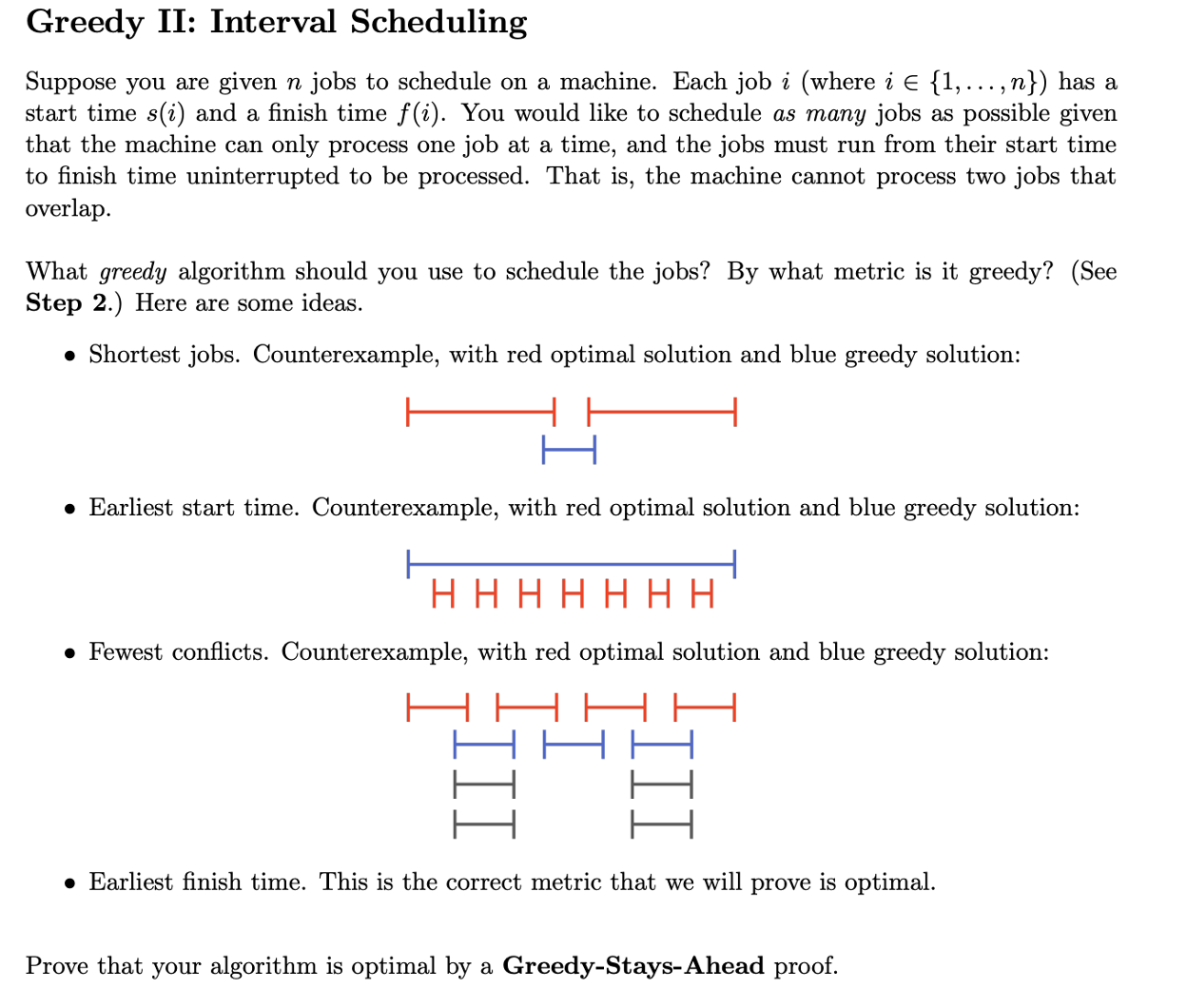

This is a picture of my typed and filled-out "lecture notes" version that I post after class.

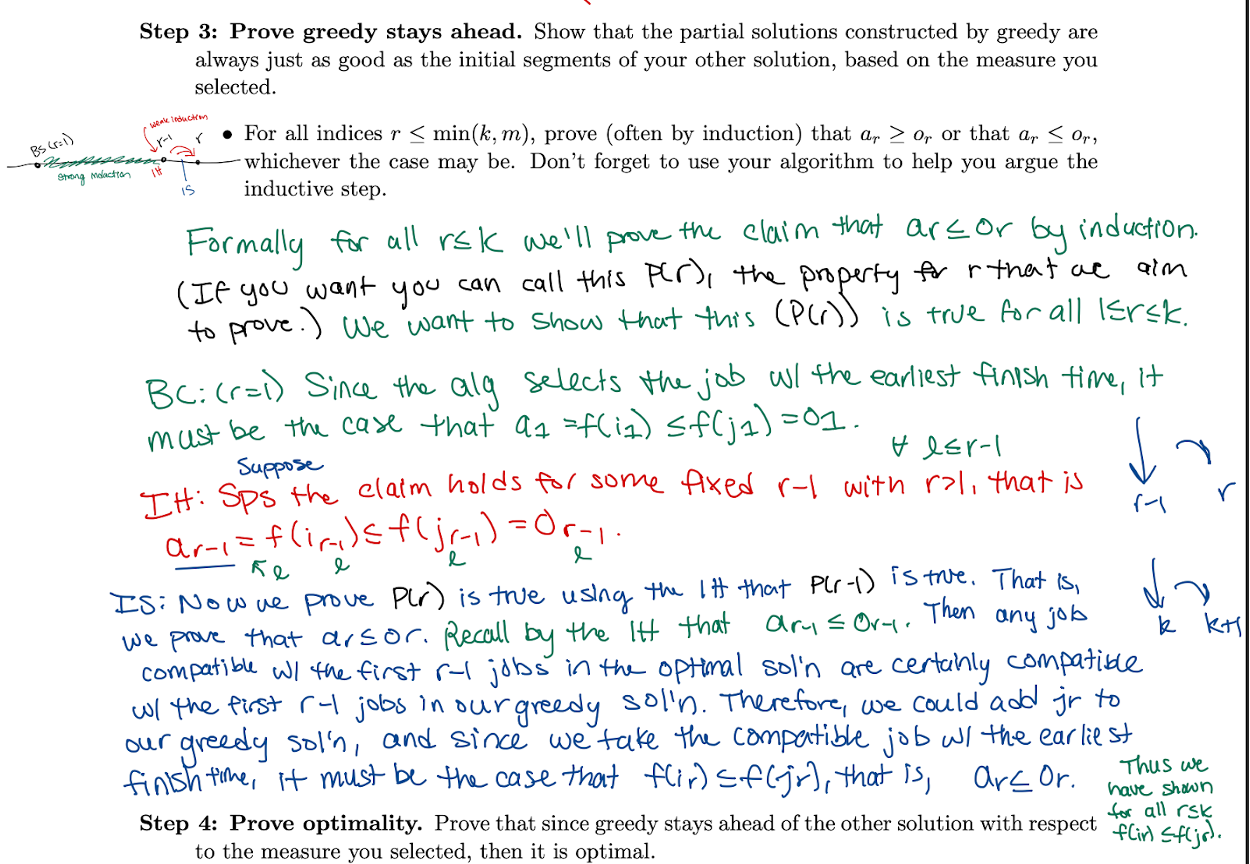

Here is an image of a part of the worksheet that I just lecture through. I may take ideas from the class ("what proof idea should we use here?" or "what comes next in our induction proof?"), but I'm standing at the front of the class writing and explaining as you would on a board, as opposed to the portion where I'm running an in-class exercise. At some points of the class where they're more used to certain problems or proof techniques, I could imagine saying "take five minutes with the people around you and try to prove this," though, and then taking ideas from the class to put the proof together.

All of my worksheets and filled-in lecture notes can be found on my course websites, which I use both for my undergraduate Algorithms for Data Science course and graduate Algorithmic Mechanism Design course.

Adaptation:

To the best of my knowledge, at least four other instructors in my department have also adapted this method for their large undergraduate mathier classes, and at least two friends at other universities as well. Here are some of the comments I've heard from them:

- Projecting on the iPad allows you to focus more on what you're saying and looking at the students for responses, rather than having to turn around from the board. It's far better.

- This system can be used to take attendance in a totally extra credit way.

- It's a good way to get students to actually engage with rhetorical questions.

- It forces one to think about the design of lectures and to make them more interactive during the design process.

Participation Cards

This idea of participation cards was invented by my colleague who excels at all things pedagogy and has been a bit of a mentor to me, especially in motivating and managing TAs (another incredibly challenging new skill to learn as junior faculty!): Kevin Gold.From my perspective, I like to treat undergraduate students as much like adults as possible, allowing for diverse preferences, subject to the fact that sometimes students just haven't developed enough self-discipline to self-impose the structure necessary to succeed at that stage, and need us to help impose it for them. To this end, I do not require attendance, as I want the student who learns better on their own to be able to succeed as well. I do require participation, but only for 5% of the cumulative grade, and in the following flexible way. (I'm sure there is a more tech-savvy way to do it, but this works for me.) At the beginning of the semester, I print out index-sized cards with each student's name on them. I then set a number of class periods so that approximately 15-20 people would participate each class if all students were to participate. E.g., for a class with 60-80 students, I would set a "participation period" as 4 classes. Students have four classes to participate during class -- ask a question or answer a question -- and then they turn in their card to me at the end of class. (I do not disrupt the class to collect cards in the middle of lecture--too many students!) If they have to miss class during that time, no worries, as long as they can attend and participate in at least one. Each period is worth 10 points on grade scope, and they get 10 points if I have their card, and 0 otherwise, and then I average the points out to that 5% of their grade.

The perks of this method are two-fold. First, introducing it on day one, it sets the tone of "get rid of this card in your hand by participating to get that chunk of your grade." It breaks down the engagement barrier and gets students in the habit of asking and answering questions. It helps regulate more even engagement because you can say things like, "someone who hasn't turned in their participation card yet...?" And every time you hand the cards back to start a new participation period, it revitalizes the class engagement. It works extraordinarily well. The second thing it does is, in combination with not taking attendance, it avoids all complaints and emails about not being able to attend class, excuses to such, complaining that they participated more than you think and you didn't use objective metrics, etc. This is an incredibly objective metric that I haven't had argued with in two years of using it.

Other Ideas from the Article

As I've said, this article on engaging a diverse classroom really inspired most of my teaching approaches. On the first day of class, I mention that we'll use hand raising and try to keep participation to an equitable level, in this way I am "explicit about promoting access and equity for all students." The hand raising works well, but obviously participation levels still vary.

I do "learn or have access to students' names." This is something I work very hard at. I give the students a "Homework 0" on gradescope that is mostly just to help them understand what I expect them to know for the class, and it includes three additional questions: what is your name in the [university system], what is your preferred name, and upload a picture of yourself that actually looks like you. The whole Homework 0 is just for participation credit (it counts as an additional participation period). I then use these answers to make myself flashcards in Anki and regularly review and practice learning the students names. I don't have perfect recall, but I put enough time into it that it makes a difference in the classroom environment. The students have repeatedly told me how much they appreciate it. The tip to put a fixed amount of time into learning students names, in addition to the article, also came from Kevin Gold.

Managing Course Staff

Once more I draw on advice from Kevin Gold. When I began teaching, I crowdsourced some advice from the site formerly known as Twitter, where people were adamant that students need their expectations very clearly set from the get-go. What I wish they had also mentioned is that TAs also need their expectations very clearly set from the get-go.I now have a document for my course staff including the following things, all inspired by a presentation Kevin once gave us on managing TAs:

A paragraph describing and motivating what our class is and what our job as course staff is and why it's important (e.g., this is the class that turns them into algorithmic thinkers; if very important that we provide prompt feedback on their attempts to help them learn these skills!). The priorities I would like my course staff to use as they TA and grade (learning, equity, student well-being). The responsibilities (expectations) of my course staff in their various positions (course staff meetings, recitations, grading, office hours, and what these entail). The tools I use and for what (Piazza, Gradescope). The reason why these are so important is that then you have something to refer back to if expectations are ever not met, and clear lines to draw if, unfortunately, you need to begin the path of termination. Following up with clear communication and expectations not being met and the motivation of why these expectations exist can avoid a lot of that mess.

Policies

I presume anyone who's been around the block has figured out to minimize for minimal excuse-emails, but for the new junior faculty, you might find these useful. Some I stole from friends' syllabi, or a twitter thread I posted asking for advice when I first started, or a few I figured out since.Attendance: Don't take it. That's asking for excuses. See my participation method above.

Late Assignments: I just give 4 late days for the whole semester, at most 2 can be used per assignment so that I can release solutions and grade on a reasonable timeline, and "only an integral number can be used per assignment" (yes unfortunately this needs to be specified). This way I don't have to worry about "I'm sick" or "I'm away at a track meet" or individual excuses unless it really requires an accommodation, in which case they usually are going through the Accommodations office at that point. Shout out to Matt Weinberg who I stole this from.

Drop an assignment: I don't. I want them to care about every assignment, so I down-weight their lowest assignment to 30%. I think I got this from Jason Hartline.

Regrades: I give 7 days for regrades, only through gradescope, and say a written explanation of why it was graded incorrectly (as opposed to insufficient partial credit) is required. I've more recently heard a better phrasing which is more like the rubric is final, you can only submit a regrade request if the rubric is misapplied. Thanks to Chamsi Hssaine for this.